A Supposedly Female Thing I’ll Never Do Again

“HAVE YOU EVER heard of spooning?” the fifth Dragon King of Bhutan asked me. He addressed me by my deadname, which at that point, even a decade before I transitioned, friends didn’t—it was my boyfriend who’d introduced us, and he thought the masc “Mac” they called me was too queer for nobility. And so, the night we lay down next to each other in a tent set up on his royal lawn, King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck didn’t know that I went by a man’s name, much less that I was a man, when he asked me repeatedly to hold him.

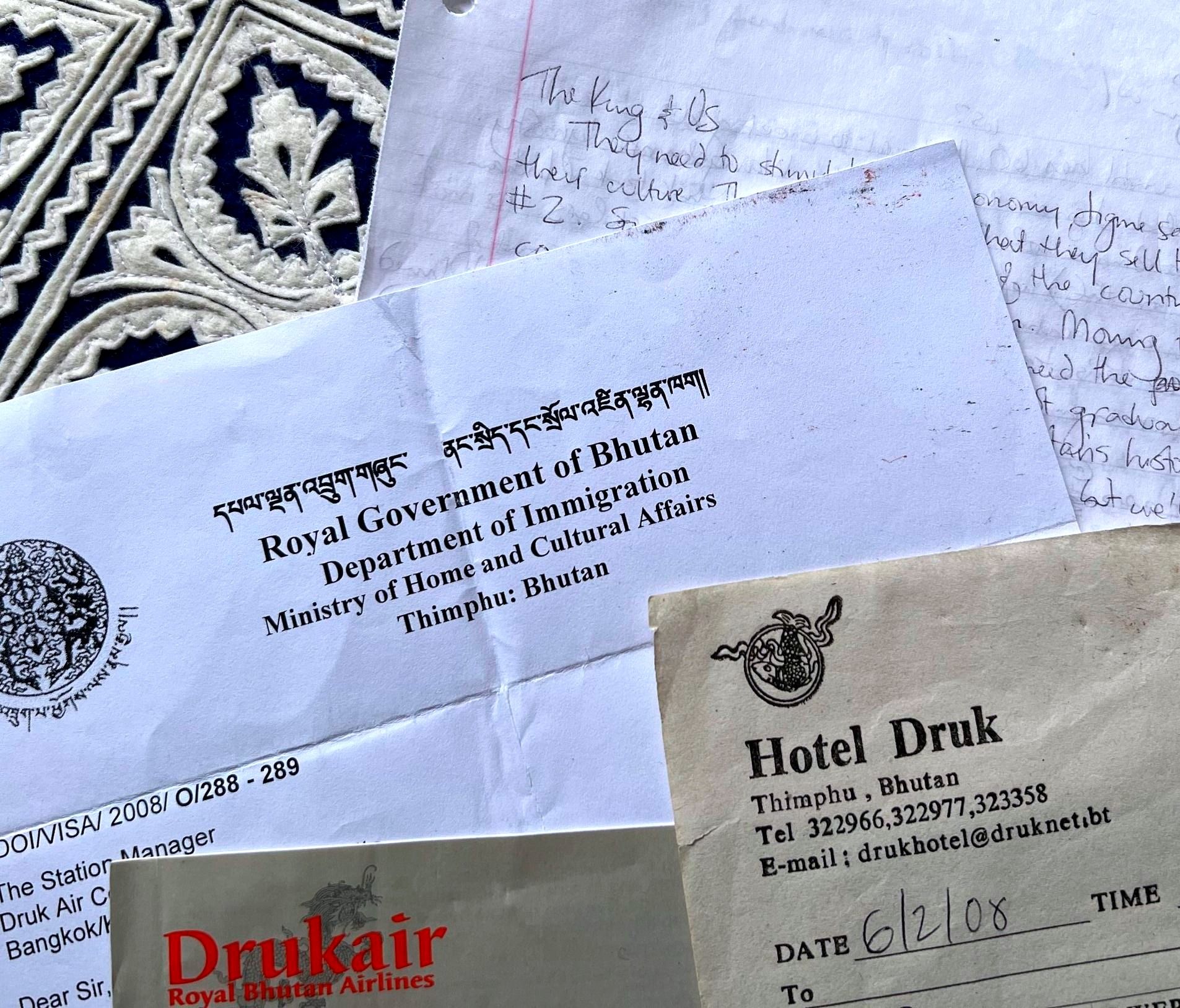

However much I was usually pretending to be a lady then, fifteen years ago, I was pretending extra hard on that trip. Everyone insisted. I’d arrived in pants, and the officer from the Ministry of Economics who picked us up at the airport soon took my then-boyfriend, Isaac, and I to a traditional-clothes shop to outfit me in a floor-length wraparound skirt that was hard to walk in with multiple layers of blousy tops. It’s true that we were there to see the king, but not in an official capacity. He’d been a prince when he and Isaac had met in boarding school in Massachusetts; they’d smoked cigarettes in the woods together. Now, we were meeting His Majesty, “HM” as the affable economics officer called him for short, to hang out. The officer had run Isaac through the official bow for when they reunited, and he’d practiced it over and over, nervous. But then our first night in town we went to see the king play a friendly basketball game in the local gym, and when we were brought to him afterward, he grabbed Isaac into a sweaty hug.

Afterward, we drove around. “I’m single,” the king told us, adding with a bit of a sheepish laugh, “and ready to mingle. Is that what they say?” The next day, we met him in a white gazebo tent for tea and sandwiches and sesame cakes topped with candied pineapples or oranges and raspberry sauce. He was elaborately robed and wearing traditional Bhutanese boots in yellow, the toes chunky and upturned like the bow of a ship, on a break between whatever a king does all day. (“It’s an extraordinary amount of reading,” he said at some point. “It’s like ninety percent of the work is reading. We’re reading everything, all the time.”) The day after that, he briefly joined us and some government staff outside to lob a metal lawn dart while holding a Heineken, looking hot in a traditional grey robe with slicked-back black hair. He was 27, and so was I. He was the youngest head of state in the world, and I…was not.

Bhutan had just had brand-new elections for its brand-new Parliament. In the next few weeks, it would have its first national elections ever as it transitioned from a full-blown monarchy to a constitutional one. When the king was busy, which was most of the time, we were escorted around the countryside on rough, narrow mountain roads in a shiny black Land Rover. I remember much of the landscape feeling empty, the unforested swathes dry, between our destinations. We visited a fancy new hotel. A museum with lots of armor, and tea kettles and stamps. The economics officer, seated up front with the driver, put in a never-ending series of techno CDs as we toured. At some point, I expressed that it was music usually only heard in gay bars. Isaac said I was being unfair, and then on came a remix of “It’s Raining Men.”

“This is gay?” the officer asked.

Maybe it was my heightened sense of my gender role that led me to pick “American Woman” for karaoke when he took us our second night to the Twilight Lounge, a tight, dark bar in the capital, with a newspaper editor and an assistant to the king. They waltzed in and set up with copious amounts of coffee and cigarettes at a table they probably sat at all the time; when the bar started filling up and karaoke started, people watched them like they were the scheduled entertainment. They got up to perform over and over, Bon Jovi and Judas Priest and Queen, the patrons clapping and even requesting that they do specific songs. Aerosmith. Radiohead. Marvin Gaye. I’d done “We Built This City” early on, and it had droned on awkwardly; people didn’t know it, and the big, corporate-rock noise that makes it fun didn’t translate to the simplified karaoke-machine cover. I’d redeemed myself, the sole supposed white girl in the establishment, with Joan Jett’s “I Love Rock and Roll,” which I’d never done but guessed based on the crowd’s favorites would go over.

And so it did.

I’d put my regular clothes back on. I got warm inside the bar in the cool Himalayan night and took off the hoodie over my strappy black tank top with a built-in shelf bra, a skin-tight underlayer I wore incessantly like a security blanket, like a second skin—like a binder. By the time I stood up and did “American Woman,” I was popular. There may not have been an actual American woman for miles; I didn’t see one all four days we were in the country, which at the time kept visitor numbers famously low. His Majesty’s personal assistant asked me to do some American moves, and some drunken hip-rocking seemed to fit the bill. I’d been ordering Bhutanese whiskey, which I was told was made with some famous Scottish peat, over ice with lemon, which is how I was told to drink it. I was hammered. “Let’s hear it for the American woman!” the newspaper editor yelled into the mic when I was done with the song, to wild cheering, and I dropped my head and long, fair hair and bowed.

Two months ago, a published study of 124 men who are trans in Bhutan—which, according to the journal article, is believed to be nearly all the men who are trans in Bhutan—found “high rates of stigma, discrimination, and interpersonal violence.” That’s what a study would find on the West Coast where I’m writing this now, too, although in Bhutan, they can’t even change genders on IDs. Just this month when I got a new driver’s license in Washington, the DMV employee told me I could pick mine, male or female or nonbinary, no questions asked. In 2019 when I changed it in California, I’d needed certified court orders to do it. When I changed it on my passport the year after that, I needed those plus a letter from a physician saying I’d been examined and determined satisfactorily male. (Neither of the above is still required, so, #GodBlessAmerica. #Progress.)

Bhutan didn’t legally decriminalize gay sex until 2021, more than a decade after I rocked the Twilight Lounge with my ex-boyfriend. So technically, and certainly if I’d been inhabiting my current body, what happened next at the hotel according to my journal was illegal:

“We go home, fuck, pass out.”

“THAT’S THE KIND of thing you can do when you have boobs,” I said to a new cis gay friend this spring about holding a king who wouldn’t have “let” me if I hadn’t. I found myself frequently thinking about, and therefore telling, this story over the several months I went to a string of gatherings consisting almost entirely of cis gay men. I wouldn’t have been welcomed in Bhutan with a boyfriend (who, also, wouldn’t have been my boyfriend) then looking like this—and I wouldn’t be welcome at these gatherings, now, looking like that.

“It is so intense,” I said to an old cis gay friend this week as I was working on this piece, understating it wildly, “to reconcile how my life wouldn’t have happened if I were actually me.” En route to the gay gatherings, I’d seen my second ex-husband for the first time in five years, and once we were both drunk finally said out loud to him, “You wouldn’t have married me if I looked like this.” I wouldn’t pick him now, nor Isaac, either, but sitting across my wood dinette table from my former spouse, I felt my heart break when after a long, heavy pause, he shook his head slightly and acknowledged, “No.”

“I think we met at another gathering,” many, so many cis gay men said as they approached me for the first time this spring, bringing back the trend I’d only recently escaped of people mistaking me for someone else. In some cases, they were mistaking me for another transsexual. In one of those cases, the person mistaking me for another transsexual had recently been my own fucking therapist.

“No,” I replied bluntly a few times, “I wasn’t allowed here before because I looked like a woman.”

“You are very beautiful,” the aunt of the economics officer told me on our third day in Bhutan. It was the lunar New Year, and the officer took us first to his parents’ house for a breakfast feast of yak stomach, potatoes and cheese, pork, red and white rice, milk tea, and the ubiquitous tea with yak butter people had served us when we’d stopped at their humble abodes on our meandering tours. The day before, we’d stopped at a few very wealthy people’s houses as well, during parties celebrating the king’s conferring scarves of honor on the prominent men who owned them. There, the women wore high heels with their long multicolored skirts and traditional short silk jackets, and we were offered Bacardi. Inside every single house, rich or poor, there was a picture of the king on the wall, young and stately and handsome. “Prince Charming,” Thai newspapers called him when he went for a diplomatic visit, before his father, who’d been king since he was 16, stepped down early and left him the throne.

The economics officer’s parents helped put me into my Bhutanese-lady dress. My long hair spilled over the embroidered black jacket and turquoise blouse underneath. “You are very beautiful,” another older woman told me at the Royal Takin Preserve, a park for the adorably dumpy endangered beasts, where we went next. Her family was having a holiday picnic on the grounds. They poured us glasses of homemade wine and kept refilling them, abundance that was important to offer as well as to receive on the first day of the new year, setting the tone for the next 354 days. It was strong, and we were drunk by noon. Isaac and the officer were hungover by the time I sent them out after lunch to find me some tampons, for which they had to scour what seemed like every store in the capital.

Dicks were easier to come by. Painted on the sides of many buildings, often spewing semen or fire, the symbols of protection and fertility were also carved, decorated, and sold in shops. Our fourth and final day, we drove up a mountain pass where the economics officer told us Buddhist hero Drupka Kunley subdued a demoness the same way he supposedly bestowed enlightenment on any good-looking woman within reach: with his dick. He called it the Flaming Thunderbolt of Wisdom. (I mean, relatable—if in a much less misogynist and manipulative way.)

“Boys versus girls,” someone said, and it may have been the king himself, when we gathered later that night for the farewell karaoke party he was throwing us on the grounds outside his house, in the compound of Tashichho Dzong. (“Tonight,” he had decreed earlier, when we met him briefly for salmon sandwiches and hot soup with chunks of Bhutanese cheese, “everyone is wearing jeans.”) Two giant fires burned in metal fire rings on the lawn, the heat for the evening. Two long tables were set up, one with mountains of popcorn, peanuts, and potato chips, another with more bottles of wine and booze than 100 people would know what to do with, let alone the eight of us in attendance—there were not that many people in a tiny farm country with whom the revered hunky sovereign could let loose. He’d been envious when we told him we went to karaoke at the Twilight Lounge. I had told him as well about attending outdoor movies in San Francisco’s Dolores Park, and when we arrived at his party, there was an enormous screen with a projector playing History of the World. But the film was turned off in favor of projecting karaoke lyrics before long, and someone announced that we would sing in a battle between the sexes.

The king was, it turned out, kind of a mic hog. He sang one Elvis song after another, no breaks, which isn’t how karaoke works at all. “Are You Lonesome Tonight,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” “Suspicious Minds.” “Viva Las Vegas.” “In the Ghetto.” He would not relinquish the microphone. “Maybe it’s glued to your hand,” one of the two women on my team called out to him, and I loved her.

The karaoke machine we were using had a voice-tracking function that gave a score at the end of every performance. I got up and did “…Baby One More Time” and got a 97, the highest one yet. The men got up and tried to beat it, eventually tying by screaming the lyrics of “Born to Be Wild,” whereby we learned that yelling scored as well as accuracy. The women and I did “I Love Rock and Roll” together, warmed up as I was from doing it the other night, and with excellence, rather than loudness, got a 98.

The Bhutanese men, one of whom identified as “a professional man of leisure,” constantly refilled my glass. I got so drunk that when I went inside to pee in the king’s bathroom, I leaned over the sink counter with his pomade on it, looked in the mirror, and couldn’t recognize my face. Or I got drunk enough, it might be more right to say, that I could recognize that I couldn’t recognize my face. Back outside at the party, I sat on the ground and drank cup after cup of water. I ate food from enormous silver platters brought out by royal servers. When at some point I asked where the king was, the women pointed to the small, low white tent someone had set up near the projector.

It was just tall enough to sit up inside. I poked my head in to find the economics officer lying on the left, a big lump of blankets on the right; the king had pulled them over his head. Isaac crawled in behind me and we both lay down between them, the four of us packed in, chatting, Isaac feeling uneasy next to me until he soon left to sing “Country Roads” after trying to harangue me into coming with him. Instead I stayed, there next to the unified head of Bhutan’s spirituality and political system, and told him I was queer.

He’d poked his head out of the blankets so we could talk. He said he didn’t believe me. For much of high school, some of college, and again after grad school, I assured him, I had dated another person with a vagina; I again had a girlfriend, I told the king, when I’d met Isaac. This led to an I guess predictable question about how two women have intercourse, and a brief explanation that did not prominently feature but did include strap-ons, about which he responded, bless him: “They don’t seem necessary. Two people seem sufficient.”

It was well before this point that the economics officer next to me had started touching himself. It was under covers, but obvious, both in movement and in the breath-caught way he conversed with us occasionally as he did it. Whether Jigme was following boarding-school rules of ignoring it or genuinely didn’t notice, I can’t say. He did seem somewhat in his own world as he continued to drunkenly talk and then asked me if I’d ever heard of spooning.

I had, of course, and told him so. And felt like that resolved that. And the officer next to me continued to pant, making rough, jerking movements beside me, which I not only ignored but decided must not be happening, right?, because he couldn’t possibly be doing this in this proximity to this monarch, and also I was brainwashed since birth to believe that the perception of cis men, even ones who aren’t king, is reality so if the king of Bhutan didn’t think anything was happening, then I guess it wasn’t. “I can’t believe you know what spooning is,” he was saying instead. And again, in a bit: “I can’t believe you’ve heard of spooning.”

I told him he was being absurd. I said I didn’t know who he thought made the term up but I was American as he knew and everyone in America knew what spooning was, but since he continued to press it I threw the king of Bhutan a bone and finally asked: “Do you want me to spoon you?”